how cultural narrative is constructed in archives

>

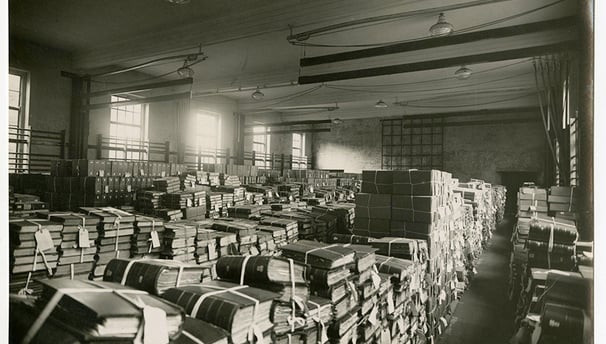

Everything which is collected, preserved and made available to public is dictated by main cultural narrative in this particular community and society. That means that at the same time this cultural narrative can be shaped and re-shaped based on the information preserved & communicated to society. Therefore, interested parties (institutions, state, authorities, power-holders, political parties etc.) can include/exclude objects and information in/from archive based on their intention to change main cultural narrative to the desired direction. Through such actions as:

increasing/decreasing funding provided to institutions & organizations;

changing «archivability» policy, making it more strict and dependent on particular institution in power;

adjusting laws around data security and access of public to archives;

supporting pigeonholing & classifixation of a certain nature, which leads to the exclusion of artefacts undesirable for the state machine from the archive;

identification and interpretation of collected documentss or objects based on state regulations etc.

a state transforms the archive to the product of a judgement, the result of the exercise of a specific power and authority. The archive, therefore, is fundamentally a matter of discrimination, selection and control, which, in the end, results in the granting of a privileged status to certain pieces of information, and the refusal of that same status to others, thereby judged «unarchivable». It‘s then a status and a tool of society manipulation, rather then a repository.

There can be archives of just about anything. But it also seems to be the case that archival reason does tend to privilege certain kinds of truth as against others; or rather, archival reason tends to problematize a certain kind of reality as being basic to its struggle for truth.

>

The cultural consequences of colonization can be far-reaching and have significant impacts on the societies, cultures, and identities of the colonized people. Colonization often involves the imposition of the colonizer‘s culture, language, values, and norms onto the colonized population. The colonized cultures may be suppressed, devalued, or even prohibited, leading to the erosion of traditional practices, beliefs, and knowledge systems. This can be made by enforcing policies and practices that aim to assimilate the colonized population into the dominant culture. As a result, traditional knowledge systems, including oral traditions and spiritual beliefs, may be devalued or dismissed by colonizers. This can result in the erosion and loss of valuable cultural knowledge that has been passed down through generations.

When colonial-era records are widely accessible while the traditions and narratives of colonized peoples are excluded or underrepresented in archives, it perpetuates a power imbalance. It reinforces the marginalization and erasure of indigenous cultures and perspectives, reinforcing the notion that the colonizers‘ narratives and experiences are more important and valid than those of the colonized. Such narratives often downplays or dismisses the contributions, experiences, and resistance of colonized peoples, further entrenching colonial perspectives, which can lead to distorted representations of their cultures. Without access to their own narratives, histories, and cultural practices, colonized communities may face misrepresentation, stereotyping, or oversimplification in the archival records, perpetuating colonial biases and misunderstandings.

To address these issues, it is important to promote inclusive archival practices that prioritize the collection, preservation, and accessibility of colonized people‘s traditions, narratives, and knowledge. This involves actively seeking out and incorporating diverse voices, experiences, and perspectives into archival collections, ensuring that the archives reflect the full breadth and richness of human history. Additionally, engaging in collaborative and participatory approaches with colonized communities can help to empower them in the process of documenting, preserving, and interpreting their own histories.

The last can only be made possible by incorporating larger human resources in archives, which is crucial for promoting inclusive practices and addressing the issues related to the accessibility and representation of colonized people‘s traditions and narratives. Adequate funding from the state is essential to support the archivist community and enable them to undertake the necessary work. By allocating sufficient resources to archival institutions, governments can ensure that there are enough archivists and staff members to effectively manage, document, preserve, and provide access to archival materials. This includes hiring professionals with diverse backgrounds and expertise, including those with knowledge of the cultures, languages, and histories of the colonized communities.

State authorities are usually not interested into more adequate and fair representation of colonized people‘s traditions and narrative, as this may lead to the revelation of the age-old cruelty and injustice that any colonization entails, which can challenge the dominant cultural narratives and may be perceived as a threat to the image and reputation of the state. It can be driven by political considerations, fear of public backlash, concerns over national identity, or a desire to maintain control over the cultural narrative. Acknowledging the injustices of colonization and promoting more inclusive archival practices require a willingness to confront difficult truths and engage in critical self-reflection.